Ever spent a long morning wondering whether to use “fewer” or “less”?

Ever spent a long morning wondering whether to use “fewer” or “less”?

The Economist wrote this on the subject this week:

“David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest featured the Militant Grammarians of Massachusetts, who boycott stores with signs reading “12 items or less”. A few vigilantes have defaced such signs in real life. What is the distinction, and why does it matter?”

As is common knowledge, nouns can be “countable nouns” or “uncountable nouns”.

Countable nouns are usually distinct things that can be counted, and take a plural: think “companies”, “law suits” or “bottles of water”.

Uncountable nouns cannot usually be counted or made plural: think “information”, “Furniture” or “water” *.

Under the traditional rule, “fewer” goes with countable nouns and “less” with uncountable nouns.

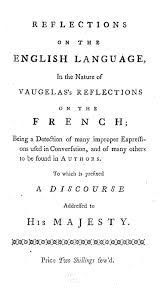

Hence “My colleague has fewer cases than I do”, but “My colleague has less work than I do”. The rule was first proposed in this form in 1770 by Robert Baker in Reflections on the English Language.

But Baker expressed this as a preference, not a rule, perhaps because there are certain grey areas (what’s new, you might ask).

In spoken English, particularly in informal surroundings, this rule is sometimes broken. “I’ve lived here less than three years” sounds and feels more natural than “I’ve lived here fewer than three years”. And “less” is almost always more natural than “fewer” after the word one, in sentences like “that’s one less thing to deal with”. Both of these examples go against the rule we have just uncovered, so, as usual in the pursuit of correct English usage, it is wise to be aware of the rule, to be aware of the exceptions to the rule and to be aware that English is a quixotic and multi-layered thing of beauty..

*They can very occasionally be counted, as in when a fancy restaurant decides to offer several different “waters”, but “water” in ordinary use is otherwise as uncountable as equipment, news and coffee)

There are evil forces at work trying to remove the hyphen from our writing, but some of us are putting up brave and solid resistance. Here is a brief clip from an article in the FT Innovative Lawyers series. Look at how the hyphens shine:

There are evil forces at work trying to remove the hyphen from our writing, but some of us are putting up brave and solid resistance. Here is a brief clip from an article in the FT Innovative Lawyers series. Look at how the hyphens shine: